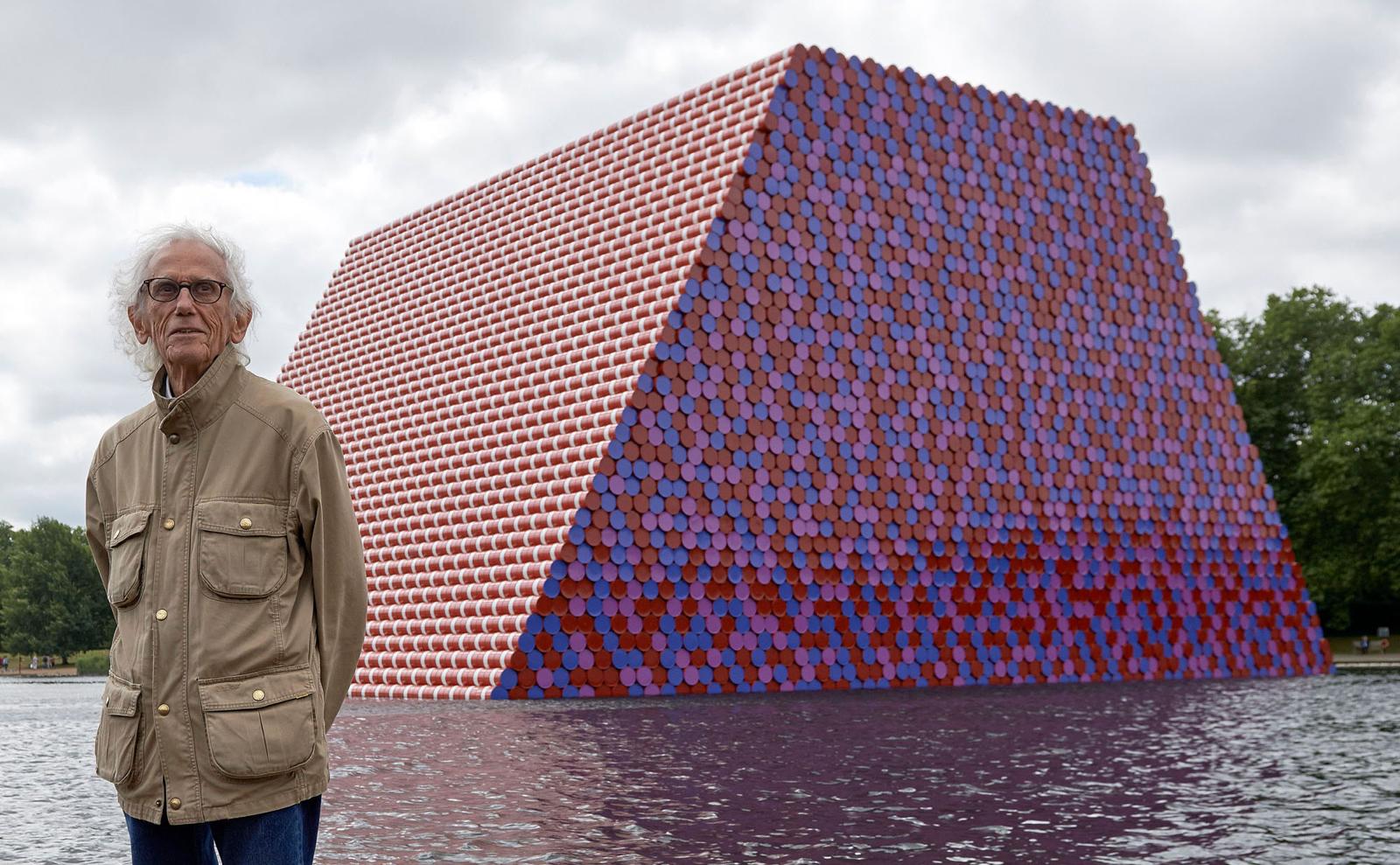

Christo Vladimirov Javacheff, known as Christo, was one of the most recognizable artists of the 20th and 21st centuries for his radical approach to environmental art. Born in 1935 in Gabrovo, Bulgaria, Christo left an indelible mark on the world of contemporary art despite the fact that his works were temporary in nature, designed to exist only for a limited time and then disappear without leaving any material trace.

From Bulgaria to Paris, then to New York

Christo's life has been marked by escape and movement from the very beginning. After studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Sofia under a communist regime, he managed to flee to the West in 1957, settling first in Vienna, then Geneva, and finally Paris. It was in the French capital that he met Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon, an artist with whom he would share his entire personal and professional life. The two began collaborating in the 1960s, although Jeanne-Claude would only be officially recognized as co-author in the 1990s.

An ephemeral yet monumental art form

Christo's works are distinguished by one fundamental characteristic: they are not designed to last. The artistic interventions he has created, often together with Jeanne-Claude, are large-scale, site-specific, temporary installations involving buildings, natural landscapes, and urban infrastructure. These are complex projects that require years of preparation, permits, negotiations with authorities, and technical and financial support. But in the end, their physical existence lasts only a few days or weeks.

One of the unique features of the couple's work is that their projects were never financed with public funds or sponsorships: the entire cost was covered by the sale of sketches, preparatory drawings, and other original works. This model guaranteed them complete creative and managerial autonomy, a crucial element in their artistic vision.

Major projects

Among Christo and Jeanne-Claude's most famous works are installations that have involved some of the world's most iconic architecture and landscapes. The Wrapped Reichstag (1995) in Berlin, where the German Parliament was wrapped in 100,000 square meters of silver fabric, is considered one of their most powerful works, both symbolically and visually. The project required 24 years of negotiations before authorization was granted.

Other significant interventions include:

• The Pont Neuf Wrapped (1985), in Paris, where the oldest bridge over the Seine was covered with sand-colored fabric.

• The Umbrellas (1991), with 3,100 large umbrellas installed simultaneously in California and Japan.

• The Gates (2005), in Central Park, New York, consisting of over 7,000 orange structures that followed the paths of the park.

• Floating Piers (2016), on Lake Iseo in Italy, a floating bridge accessible on foot that connected the mainland to the island of Monte Isola. In 16 days, the work was crossed by over 1 million people.

The meaning of temporary art

The value of Christo's works lies not in the artistic object itself, but in the process, in the temporary transformation of a public space and in the collective experience it generates. For him, art had to be experienced in the present, without mediation and without the constraint of ownership. Once completed, the work was dismantled and every element recycled or removed, as if to eliminate any temptation to commercialize it. This vision clashes with the logic of the art market, but it is precisely what made Christo's work recognizable and consistent. The artist himself always emphasized that total freedom was the central point of his practice: "There is no hidden meaning. There are no messages. The work is just what you see."

The last work

In 2021, one year after his death (in May 2020), the work L'Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped was posthumously completed in Paris. Conceived in the 1960s, the project saw the famous Parisian monument entirely wrapped in silver-blue fabric, tied with red ropes.

Once again, the project took years of preparation and involved numerous experts. It was Christo's last great vision to take shape, symbolically in the place where it all began.

An intangible legacy

Christo left no permanent collections or museum pieces. His contribution to contemporary art is measured in his ability to engage the public, to rethink urban and natural space, and to assert that a work can have an enormous impact even without leaving physical traces. His career demonstrates that art can be temporary, free, public, and yet remain permanently in the collective memory.

At Artistinct, we admire Christo: we believe he was an innovative artist in his intentions and work, as well as having a great ability to institutionalize himself, collaborating with state bodies and organizations. However, we believe that art is also capable of adapting and linking itself to different market logics, creating a business that fully integrates finance and artistic culture.

Join in!

Comments