Have you ever thought that science and creativity could intertwine to transform cells, bacteria, and living organisms into true works of art? This is exactly what happens in bioart, a contemporary artistic practice that stems from the fusion of scientific innovation and artistic sensibility. In this fascinating field, artists abandon conventional means of expression to work directly with living matter: tissues, microorganisms, and biological elements in constant transformation.

The works generated in this context become dynamic microcosms, capable of breathing, changing, and growing. Through tools such as biotechnology, genetic engineering, cell culture, and cloning, they take shape in hybrid spaces such as laboratories, studios, and equipped galleries, where art and science coexist.

What distinguishes bioart is precisely the use of living organic substances as an expressive medium, manipulated thanks to the latest developments in biological research. We are faced with a still largely unexplored territory, where molecular biology and imagination come together to redefine the boundaries of artistic creation, raising profound ethical, aesthetic, and social questions about the possibility of shaping life.

The genesis of a revolution

Bioart emerged between the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, in a historical context strongly influenced by rapid developments in molecular biology. A central role was played by the Human Genome Project, completed in 2003, which aimed to map the entire human DNA and identify all the genes present in our genetic heritage: an epoch-making turning point that created new possibilities for intervening in life itself. At the same time, the growing spread of biotechnologies such as genetic manipulation, cell culture, and cloning created the conditions for the emergence of a new form of artistic expression capable of working directly with living materials.

The term "BioArt" was coined in 1997 by Brazilian-American artist Eduardo Kac during his performance Time Capsule. On that occasion, Kac had a microchip containing personal digital data, normally used to identify animals, implanted under his skin.

However, the roots of bioart go back further in time. Already in the 1980s and 1990s, American scientist and artist Joe Davis began exploring the expressive possibilities offered by molecular biology. Davis worked at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), where he collaborated with biologists and geneticists to translate artistic ideas into biological material. One of his most famous works is Microvenus (1990), considered by many to be the first true work of bioart: in this work, Davis encodes an ancient female symbol similar to a rune in DNA sequences and inserts it into the genome of an E. coli bacterium, thus creating a work of art that is only visible through scientific instruments, but is biologically active.

Some art historians, however, trace the first experiments in bioart back to the 1930s, with the unexpected contribution of Alexander Fleming. Best known for discovering penicillin, Fleming was also a curious experimenter. In his spare time from scientific work, he enjoyed "painting" with live bacteria on Petri dishes: by combining microorganisms that developed different colors as they grew, he created images and figures, such as faces or landscapes, that took shape over time. Although he was unaware that he was giving birth to a new artistic movement, his works, now known as 'bacterial paintings', can be seen as one of the first expressions of the fusion between science and living art.

The masterpieces of artificial life

Bioart has given rise to works that have left an important mark on the history of contemporary art. Among these, the most iconic is undoubtedly GFP Bunny (2000) by Eduardo Kac. At the heart of the project is Alba, a genetically modified rabbit that, thanks to the insertion of a gene derived from a jellyfish (Aequorea victoria) into its DNA, emits a fluorescent green light when exposed to ultraviolet rays.

This is not just a scientific curiosity: the work marks an epoch-making turning point, because for the first time a living organism has been consciously transformed into a work of art through genetic manipulation.

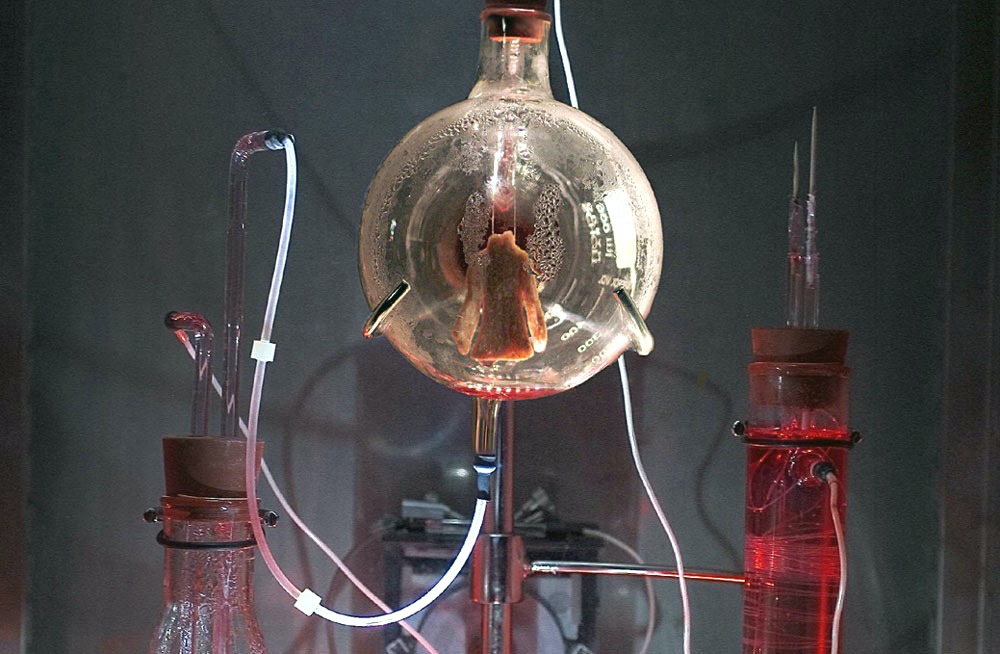

The Australian collective SymbioticA, led by Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr, revolutionized the field with "Victimless Leather": a miniature jacket grown in a laboratory from living cells, without sacrificing any animals. The work literally grows before the visitor's eyes, challenging the perception of the artistic object as a static entity. Their "Semi-Living Worry Dolls," small sculptures of cultivated tissue inspired by traditional Guatemalan dolls, represent a bridge between ancient spirituality and contemporary biotechnology.

Marta de Menezes, with "Nature?" (2000), genetically modifies butterfly wings to create patterns that have never existed in nature, demonstrating how art can push evolution beyond its natural boundaries. Each butterfly becomes a unique, living work of art, forcing us to rethink the subtle and unstable boundary between what is natural and what is man-made.

Bodies and Technologies in Dialogue

Some artists have chosen to put their bodies on the line, transforming them into living laboratories where nature and technology meet, and sometimes clash. Among these, the French artist Orlan and the Australian artist Stelarc are emblematic figures. Both use the body as a medium, but in ways that go beyond traditional body art, because they do not limit themselves to exploring pain, physical endurance, or cultural identity. Instead, their works fall within the realm of bioart, because they directly involve biomedical, surgical, and biotechnological technologies, bringing the reflection on humanity to a biological and post-human dimension.

Orlan, known for her "Self-Hybridations," staged a series of live surgical operations during which she modified her own face, drawing inspiration from aesthetic models from different cultures and eras.

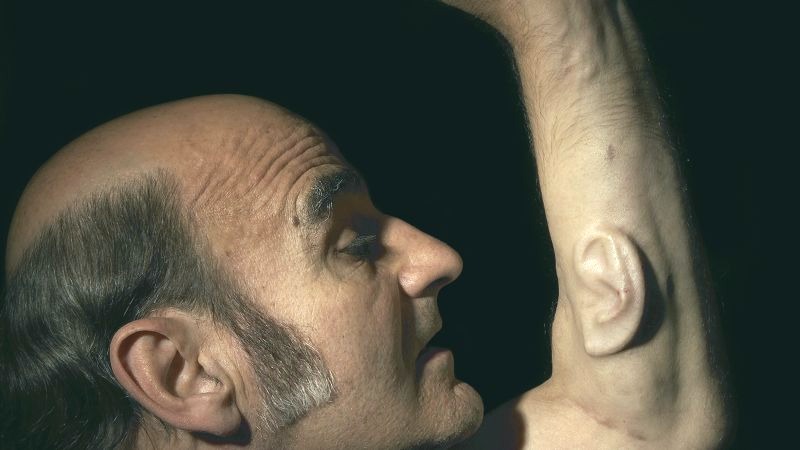

Stelarc, on the other hand, took the fusion between flesh and machine to the extreme. In Ear on Arm (2007), he had a humanoid ear, grown using tissue engineering techniques, surgically implanted into his left arm. This work is not simply a provocative gesture, but an investigation into the possibility of expanding the capabilities of the human body through technology, creating a hybrid between the organic and the artificial.

Unlike body art, which often remains linked to performative and symbolic gestures, these works fall within the field of bioart because they use tools from medicine and biotechnology to intervene on living biological matter. Their "self-experimentations" open up disturbing and fascinating scenarios on the transformation of bodily identity in the age of genetic manipulation and human-machine fusion.

Bioart is expressed through various approaches: genetic manipulation to create new forms of life, tissue culture to create living sculptures, morphological experiments to alter the shape and functions of organisms, performances and installations that directly involve the body, and the use of bacteria as pigments or constituent elements of the work. Artists such as Anna Dumitriu use bacteria and microorganisms as an expressive medium, transforming bacterial colonies into visual patterns that evolve over time.

Creativity and responsibility: the fine line

Bioart forces us to face questions that until recently seemed like science fiction: is it right to manipulate life to create beauty? Where is the line between creation and control? When a work is alive, who takes care of it, and with what rights?

Artists working in this field must deal not only with inspiration, but also with scientific protocols, ethics committees, and complex moral questions. In this sense, their practice is also a form of responsibility, an embodied reflection on what it means to "make art" today.

In a world where biotechnology and artificial intelligence are redefining the boundaries of what is possible, bioart opens up new scenarios. It does not provide answers, but it asks the right questions, those concerning our relationship with nature, technology, and life itself.

Join in!

Comments